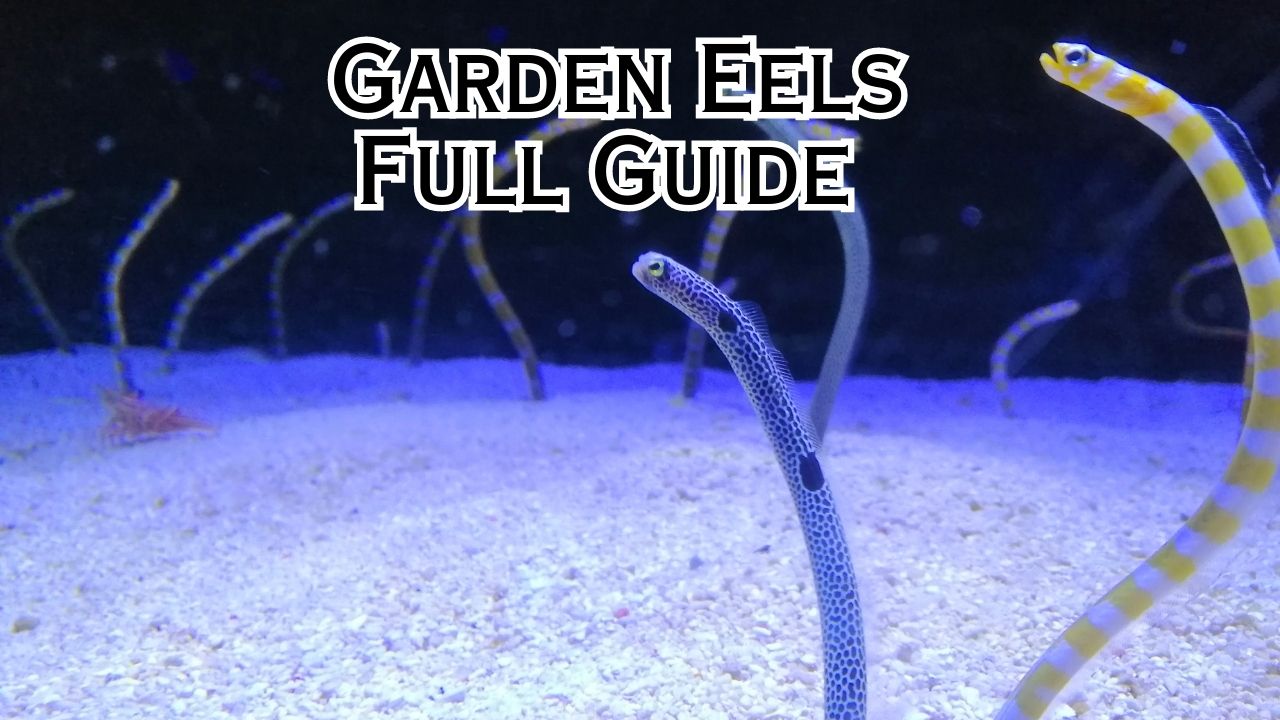

Garden eels are fascinating marine creatures, famous for their distinctive way of life. They form large colonies on sandy seabeds, swaying gently in ocean currents while feeding on plankton. Garden eels belong to the family Congridae and are closely related to conger eels. They are found in tropical and subtropical oceans around the world. This guide will cover what makes garden eels unique, from their habitat and anatomy to their behavior, diet, and importance in marine ecosystems.

Habitat and Distribution

Garden eels prefer sandy slopes and flats near coral reefs or seagrass beds, at depths ranging from 23 to 150 feet (7–45 meters). They thrive in areas with strong currents, which bring them a steady stream of food. These colonies can have dozens or even hundreds of eels packed together, each in its own burrow. Common regions include the Indo-Pacific, Red Sea, Caribbean, and warmer parts of the Pacific.

Their burrows are engineered marvels, with eels burrowing tail-first and using a special mucus to cement the walls. This prevents collapse even as they withdraw quickly at the slightest sign of danger—an essential defense against predators like triggerfish or wrasses.

Anatomy and Built-In Engineering

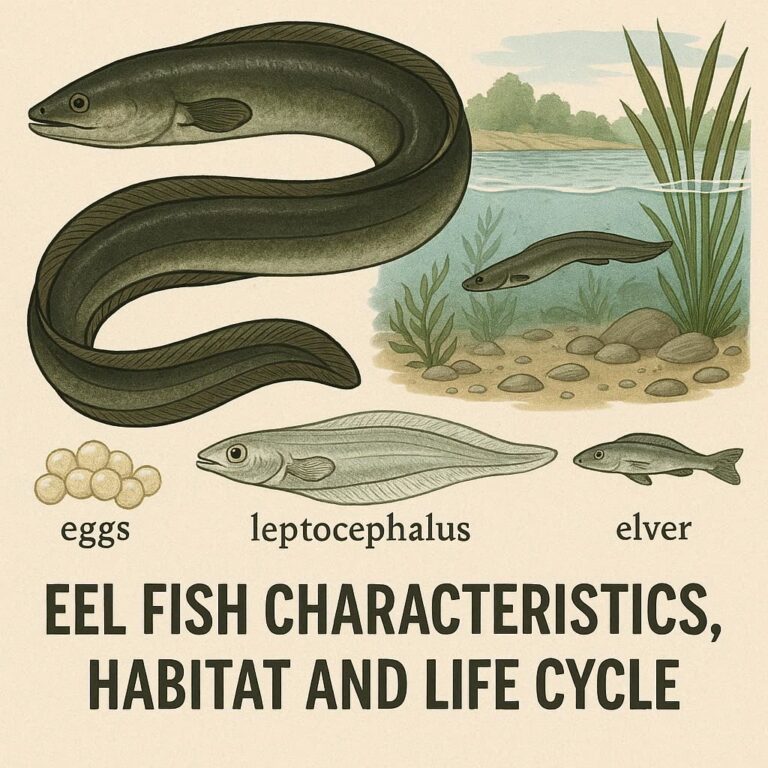

Garden eels have slender, elongated bodies that can grow up to 16–24 inches (40–61 cm) in length. Their heads and upper bodies are usually visible above the sand, while most of their body stays hidden in a burrow. Each species has unique markings and features—a common example is the spotted garden eel (Heteroconger hassi), which displays several prominent black spots along its white body.

A gland near the tail mixes mucus and sand to create a tough, flexible tube. When threatened, the eel contracts its body in a split second, retreating deep into its burrow and often sealing the entrance with a quick mucus plug. This keeps out predators and preserves a breathable space while hiding.

Social Behavior and Colony Life

Garden eels are social animals. In the wild, colonies form gardens where eels sway together, all facing the same direction to intercept plankton. Each eel has its own burrow, keeping enough distance from others to avoid competition, but close enough for social interaction—especially during the breeding season.

Eels rarely leave their burrows; instead, they stretch just a third of their body length above the sand, swaying and retracting as needed. They watch for predators with their keen eyesight and can disappear into the sand in less than a second. Males sometimes compete aggressively for territory and mates, while females choose burrows near favored males during spawning.

Diet and Feeding Behavior

Garden eels are continuous, opportunistic feeders. Their main diet is zooplankton and small crustaceans, which drift by in ocean currents. Eels snatch their food with quick strikes as it passes their burrow. They have excellent eyesight, allowing them to spot both prey and approaching threats.

In captivity, they are fed a mix of live foods including amphipods, copepods, brine shrimp, and ghost shrimp. Multiple feedings per day are recommended to replicate natural foraging and maintain health.

Breeding and Life Cycle

Garden eels use unique breeding behaviors. During spawning, males and females move their burrows closer, sometimes intertwining bodies for mating. They are pelagic spawners: fertilized eggs are released into the current, where they drift until hatching. Juvenile eels eventually settle on the seabed and dig their own burrow.

Their larval stage can last many months while floating in the open ocean, ensuring widespread distribution. Once juveniles reach a certain size, they descend to the sand and start colony life.

Aquarium Care and Conservation

Keeping garden eels in aquariums is challenging. They require deep sand beds (minimum 6–12 inches), strong but gentle water currents, and spacious tanks (at least 125 gallons for colonies). Garden eels do best in environments that mimic the wild: stable salinity (sg 1.020–1.025), temperatures between 22–26°C, and pH near 8. Seagrass and live rock offer shelter and reduce stress.

Eels can be stressed by sudden changes or aggressive tankmates. They need places to hide, ample sand for burrowing, and should be fed multiple times daily. Replicating currents and varied diets helps support their natural behaviors and health.

Most garden eel species are “Least Concern” according to the IUCN Red List, but habitat destruction and aquarium harvesting pose potential risks. Protecting coral reefs and sandy slopes ensures their survival.

Fun Facts

Spotted garden eels can create mucus plugs to seal their burrows, keeping out predators and maintaining insulation.

Colonies are so dense that there can be up to 15 eels per square meter.

Garden eels rarely leave their burrows, surviving months in the same patch of sand unless disturbed.

Their swaying movements resemble blades of seagrass, helping them camouflage and avoid detection by predators.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do garden eels make their burrows?

They burrow tail-first into sand and use mucus to cement the walls, creating a flexible home.

Are garden eels found in groups?

Yes, colonies can have dozens or hundreds of individuals in close-knit gardens.

What do garden eels eat?

They feed on zooplankton and small drifting crustaceans, snatching food from passing currents.

How do garden eels protect themselves?

They quickly retreat into burrows and can seal the entrance with a mucus plug to keep predators away.

How long do garden eels grow?

Adults typically reach 16–24 inches (40–61 cm) in length, depending on species.

Where are garden eels found?

They live in tropical and subtropical oceans—especially near reefs in the Indo-Pacific, Red Sea, Caribbean, and Pacific.

Can garden eels be kept in home aquariums?

Yes, but they need deep sand beds, gentle currents, and careful tank setup to thrive.

Are garden eels endangered?

Most species are considered “Least Concern,” but habitat loss is a growing threat.

How do garden eels reproduce?

Males and females intertwine during spawning, releasing eggs and sperm into the current for fertilization.

What predators do garden eels face?

Fish like triggerfish, wrasses, and predatory rays will dig them out or surprise them from below.

Conclusion

Garden eels are unique and captivating marine animals, famous for forming swaying colonies on the ocean floor. Their lifestyle—from building burrows to continuous feeding and colony breeding—makes them important members of tropical reef ecosystems. Protecting their habitats and understanding their needs in captivity are key to their survival, ensuring these gentle “seagrass mimics” continue to enchant both scientists and aquarists for years to come.

- https://www.mantasystems.net/a/blog/post/gardeneels

- https://wildwelfare.org/wp-content/uploads/Care-for-us-Garden-Eel.pdf

- https://www.georgiaaquarium.org/animal/spotted-garden-eel/

- https://oceana.org/marine-life/white-ring-garden-eel/

- https://dwazoo.com/animal/spotted-garden-eel/

- https://denverzoo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Spotted-Garden-Eel.pdf

- https://www.diy.org/article/garden_eel